Understanding the Bigger Picture: Macroeconomic Performance and the Well-Being of Society

In this part of the book, my goal is to provide you with detailed methods for evaluating the overall economic health of any country. While this book offers a broad overview using selected country examples, it is not possible to cover data for every nation. To support your own exploration and analysis, I have included a list of useful resources at the end of this section. These sources provide access to a wide range of reliable numerical data. If you’re interested in looking up specific countries or comparing different cases, you may find these platforms helpful. In this section, the main aim is to make economic indicators easy to understand for those who are not familiar with economic details. Additionally, since these economic figures change every year, the methods I discuss will be useful for updating your evaluations with the latest data.

Let’s embark on our journey. At the time of scripting this book, the global economy boasted a valuation of approximately 80 trillion dollars, with the United States accounting for a quarter of this sum, roughly 20 trillion dollars. But how does the U.S. command such a significant share? Does it syphon off a quarter of the world’s economic potential, hoarding it for itself? This notion hints at a discourse suggesting that if the world’s wealth were evenly distributed, universal prosperity would ensue, eradicating global hunger. But is this proposition accurate?

Historically, western powers once imposed colonial dominion over vast swathes of the globe, exploiting their resources for economic gain. However, contemporary academia in these western nations critically examines and acknowledges these past injustices. Yet, in everyday discourse, one often hears enquiries into the wealth disparity between the West and the rest of the world, with the convenient answer being exploitation. This narrative, while convenient, absolves individuals of accountability and obscures deeper complexities.

It’s important not to focus only on past problems but to stay aware of current realities. People who focus only on past wrongs may miss current situations and the reasons for their own lack of progress. Instead, we need to examine both history and the present. While many Western nations once presided over colonial empires, these systems collapsed in the mid-20th century. Consider the Netherlands, which achieved an impressive literacy rate exceeding eighty percent in the early 1700s, a milestone not attained by some nations until the mid-1800s or later. This discrepancy underscores a centuries-long lag between nations. Developing countries need to acknowledge historical injustices, but they must also look beyond them to understand the multifaceted reasons for their current state of development.

The gap or difference being discussed is not limited to just how well people can read or write. It also appears in other important areas of society, such as the design and structure of buildings (architecture), creative expressions (art), the development of cities (urban planning), and progress in technology. In other words, the divide impacts multiple aspects of life, not just education. The internet, the telescope, the diesel engine, penicillin, smartphones, powered flight, and space exploration – these groundbreaking inventions predominantly hail from western nations, epitomizing centuries of scientific and cultural progress. Exemplary urban planning, as evidenced by historic locales like Ortigia in Italy or Carcassonne in France, underscores centuries of development and innovation. These cities stand as testaments to human creativity and progress, serving as inspirations for future advancements.

However, from the perspective of underdeveloped nations, the goal isn’t to praise the West but to make thoughtful evaluations and move forward with clear intention. Societies that embrace democracy and build strong institutions have the potential to become modern and successful. Failing to do so is a setback they cause for themselves. Whether through oppressive leadership or by blindly following charismatic leaders in so-called democratic systems, the responsibility lies with those in power. Blaming past wrongs or focusing on conspiracy theories only holds back progress. The responsibility is on underdeveloped nations to shape their own future.

In regions where individuals assume responsibility and align personal visions with societal development, tangible progress unfolds. Economic analyses must henceforth be reframed within this context. The disproportionate economic prowess of certain nations, like the United States and Europe, reflects not theft but rather the cumulative output of their institutions, organizations, and populace. Economic power stems from the value generated by individuals and entities within a nation – be it through medical procedures, mechanical repairs, or technological innovations. This amalgamation of productive endeavours culminates in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a quantitative measure of a nation’s economic output over a given period.

Now, let’s explore the methods for measuring and interpreting the size and performance of national economies. Economists employ various methodologies, often centered on either income or expenditure. One prevalent approach revolves around total expenditures, encapsulating the sum of all expenditures within a nation. This demand-centric methodology serves as a cornerstone for gauging economic vitality and delineating the contours of national prosperity.

Think of a country’s economy. Like a big machine, it’s made up of several large moving parts. When we look at the total value of everything produced in that country, all the goods and services created over a certain period, we give it a name: Y. You’ve probably heard the official term for this: Gross Domestic Product, or GDP for short.

GDP is a useful way to capture the entire size of an economy in a single number. But what’s even more important is to understand what makes up that number. It’s not just a lump sum that appears out of nowhere. It’s built from four major components, and understanding these gives us a clearer view of how an economy works, how it grows, and what we can do if it starts to struggle.

The first and biggest part is private consumption, usually represented by the letter C. This is the total spending by households, people like you and me buying food, clothes, furniture, going to the cinema, taking a holiday, and so on. In many countries, this is the largest part of the economy because it’s all about everyday life.

A Quick Look at the Business Cycle: What Has Happened Over the Last 40–50 Years?

For those who are curious about how economies behave over time, here’s a brief overview of key ups and downs from recent decades. It’s a reminder that economic growth doesn’t follow a straight path – it moves in cycles, with booms and busts, expansions and recessions.

Late 1980s – Boom Years

Many Western economies, especially the US and UK, experienced strong growth during the late 1980s. This period was marked by rising consumer confidence, financial deregulation, and low inflation. But this didn’t last forever.

Early 1990s – Recession

In the early 1990s, growth slowed. Interest rates had risen to fight inflation, credit markets tightened, and some countries experienced banking crises. The result was a mild to moderate recession.

The second part is investment, written as I. This isn’t stock market speculation. It refers to real investment inside the country: businesses building factories, buying machines, or governments investing in infrastructure. These are the kinds of investments that help the economy grow in the future.

Then we have government spending, represented as G. This is what the government spends on public services like education, healthcare, roads, public salaries, defence, and so on. It’s a significant part of the economy and plays a crucial role, especially when private activity slows down.

The last part brings in the global picture: exports and imports. When a country exports goods and services and sells things to the rest of the world, it earns money. When it imports, it spends money on things it buys from abroad. We take the value of exports (X) and subtract imports (M), and what we get is net exports, or (X – M). If exports are higher than imports, this number is positive. If a country imports more than it exports, it’s negative.

When we put it all together, the basic formula for GDP looks like this:

Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

This simple-looking equation helps us understand what’s happening inside a very complex system. It also helps governments design economic policies – whether the goal is to encourage spending, boost investment, manage public budgets, or improve trade balances. These four components give us a starting point to evaluate any economy, anywhere in the world.

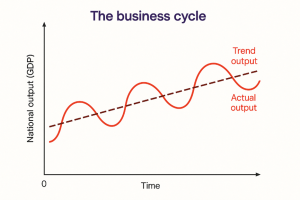

The graphical representation provided above maps out the trajectory of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over time, serving as a visual indicator of a country’s economic performance. Every nation possesses inherent economic potential, which can be assessed by examining both the total labour force and the accumulation of capital resources within its borders. An economy’s potential level represents the maximum output it can sustainably achieve when all available resources, including labour, capital, and technology, are utilised efficiently. Think of it as the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services without causing undue strain or inflationary pressures. This potential level is often depicted as a trend line on the graph plotting economic output over time.

A Quick Look at the Business Cycle: What Has Happened Over the Last 40–50 Years?

2001 – The Dot-Com Crash and Mild Recession

The bubble burst in 2000–2001. Many tech firms collapsed. The crash was followed by a brief recession in the US, made worse by the shock of the 9/11 attacks.

2008–2009 – The Global Financial Crisis

One of the most significant economic downturns in modern history. It was caused by excessive risk-taking in financial markets, especially around housing loans in the US. Banks failed, unemployment rose sharply, and governments around the world responded with emergency rescue packages.

2009–2020 – Long Recovery and Expansion

Despite the depth of the crisis, the recovery that followed became one of the longest expansions ever recorded. Interest rates stayed low for years. Unemployment gradually fell, and technological change continued, but the recovery was uneven, and inequality remained a challenge.

2020 – The COVID-19 Shock

A sudden and deep recession struck in early 2020 as the world shut down to control the spread of the virus. Economic activity collapsed, but governments responded with massive support, and most economies bounced back strongly in 2021.

2009–2020 – Long Recovery and Expansion

Despite the depth of the crisis, the recovery that followed became one of the longest expansions ever recorded. Interest rates stayed low for years. Unemployment gradually fell, and technological change continued, but the recovery was uneven, and inequality remained a challenge.

2008–2009 – The Global Financial Crisis

One of the most significant economic downturns in modern history. It was caused by excessive risk-taking in financial markets, especially around housing loans in the US. Banks failed, unemployment rose sharply, and governments around the world responded with emergency rescue packages.

2001 – The Dot-Com Crash and Mild Recession

The bubble burst in 2000–2001. Many tech firms collapsed. The crash was followed by a brief recession in the US, made worse by the shock of the 9/11 attacks.

However, the actual output of an economy rarely remains precisely at its potential level. Fluctuations occur due to various factors, leading the economy to operate either above or below its potential. These fluctuations are integral to economic life and are influenced by a multitude of internal and external forces. One reason for fluctuations is the inherent dynamism of market economies. Supply and demand conditions, consumer preferences, technological advancements, and external shocks all contribute to changes in economic activity. For example, during periods of robust economic growth, demand for goods and services may outpace the economy’s capacity to supply them, leading to inflationary pressures and an output level above potential. Conversely, during economic downturns or recessions, demand may fall, causing unemployment and a contraction in output below potential.

Moreover, changes in government policies, fiscal and monetary measures, and international trade dynamics can also affect the economy’s trajectory. Government spending, taxation policies, interest rates, and exchange rate fluctuations all play a role in shaping economic outcomes. For instance, expansionary fiscal policies, such as increased government spending or tax cuts, can stimulate demand and boost output, potentially pushing the economy above its potential level. Conversely, contractionary monetary policies, like raising interest rates to curb inflation, can dampen demand and lead to output falling below potential.

External factors, such as changes in global economic conditions, geopolitical events, natural disasters, or pandemics, can also influence economic fluctuations. These exogenous shocks can disrupt supply chains, affect consumer confidence, or alter investment decisions, leading to deviations from the economy’s potential level.

Overall, the economy fluctuates around its potential level due to the complex interplay of numerous factors, including market dynamics, government policies, and external shocks. Understanding these fluctuations and their underlying causes is essential for policymakers and businesses to formulate effective strategies to manage economic risks and foster sustainable growth.

Should the economy operate below this potential threshold, analysis utilising the formula (1) elucidated earlier becomes imperative. A shortfall in performance may be attributed to various factors, such as decreased private sector expenditures, diminished investment levels, inadequate public spending, or a deficit in international trade – where imports surpass exports. Pinpointing the source of underperformance is crucial to implementing corrective measures aimed at realigning the economy with its true potential.

Conversely, when the economy operates above its potential, it signals a scenario where certain sectors exceed their maximum capacity. This situation can lead to inflationary pressures, the formation of speculative bubbles, or unsustainable growth. In such instances, it becomes essential to implement policies aimed at stabilising and moderating economic activity, steering it back towards its sustainable trajectory.

These fluctuations in economic performance are inherent to the economic landscape and necessitate adept management to ensure stability and growth. The response to these fluctuations hinges on differing economic ideologies regarding the role of government intervention. Traditional economic theory, rooted in the principles of supply-side economics, advocates for minimal government interference, positing that market forces will naturally correct imbalances over time.

Contrastingly, proponents of Keynesian economics, influenced by the work of British economist John Maynard Keynes, advocate for proactive government intervention, particularly during periods of economic downturn. Keynes argued that relying solely on market mechanisms to rectify economic imbalances could prolong periods of recession or depression, leading to prolonged unemployment and economic hardship.

Central to Keynesian intervention is the concept of fiscal policy, wherein governments increase spending to stimulate demand and propel economic growth. However, this often necessitates borrowing to finance increased expenditure. While deficit spending can be an effective tool for revitalising a sluggish economy, prudent management is essential to ensure debt remains sustainable and manageable.

The sustainability of government debt is contingent upon its ratio to national income, with economists generally recommending that this ratio does not exceed a certain threshold, typically around 65 per cent. Exceeding this threshold poses risks to the repayment of debt and undermines the efficacy of government interventions.

In addressing high levels of debt, some governments may consider austerity measures aimed at reducing expenditure. However, such measures can exacerbate economic downturns by further contracting aggregate demand and stifling growth. Alternatively, governments can utilise monetary policy tools, such as interest rate adjustments or tax reforms, to stimulate economic activity and foster growth.

Case studies, such as Ireland’s tax reforms in the 1990s, underscore the potential efficacy of targeted interventions in driving economic growth. By reducing taxes and implementing favourable monetary policies, governments can incentivise investment and consumption, thus propelling the economy towards its potential output.

Throughout this discussion, it’s crucial to recognise that economic management is a multifaceted endeavour, requiring a nuanced understanding of both macroeconomic principles and real-world dynamics. In subsequent chapters, we will delve deeper into policy recommendations and explore strategies for navigating economic fluctuations while fostering sustainable growth and prosperity.

Frequently, we encounter discussions about the world’s largest economies, often highlighted during gatherings like the G7 or G20 summits, where leaders from the most economically potent nations convene. These rankings are typically determined by assessing the cumulative economic output of these countries in conjunction with their potential economic power. Let’s delve into the significance of these rankings by examining the table provided below.

Three-column table listing rank, country, and GDP in trillions of U.S. dollars for 2025.

| Rank | Country | GDP (trillion USD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 22.9 |

| 2 | China | 16.9 |

| 3 | Japan | 4.9 |

| 4 | Germany | 4.2 |

| 5 | India | 3.5 |

| 6 | United Kingdom | 3.1 |

| 7 | France | 2.9 |

| 8 | Italy | 2.1 |

| 9 | Canada | 2.0 |

| 10 | South Korea | 1.8 |

| 11 | Russia | 1.7 |

| 12 | Brazil | 1.5 |

| 13 | Australia | 1.4 |

| 14 | Spain | 1.4 |

| 15 | Mexico | 1.3 |

| 16 | Indonesia | 1.2 |

| 17 | Netherlands | 1.0 |

| 18 | Saudi Arabia | 0.9 |

| 19 | Turkey | 0.8 |

| 20 | Switzerland | 0.7 |

The global economic landscape is dominated by powerhouses like the United States, which alone contributes approximately a quarter to the world’s economy, with China closely trailing as the second-largest economic entity. This begs the question: Is the sheer size of an economy an achievement in itself? While a sizable economy undoubtedly grants a nation significant global influence and the ability to enact impactful policies, it’s imperative to explore the broader implications and responsibilities that accompany such economic stature.

In the realm of global influence, major economies are not only financial titans but also leverage their economic muscle to advance national interests. This can take the form of military interventions or economic sanctions, such as those imposed by the United States on Turkey in 2018. The effectiveness of these sanctions often correlates directly with the economic might of the country imposing them, highlighting the importance of economic scale in international relations.

The European Union, a conglomerate of 27 member states, many of which rank among the world’s most developed nations, stands as a testament to the collective economic power matching that of the United States. This unified economic strength underpins ambitious projects, like space exploration, facilitated by organisations such as the European Space Agency (ESA) and Airbus. These initiatives illustrate how a large economy can foster innovation and competitiveness, offering industries the scale needed to thrive and compete on a global stage.

However, the advantages of being a leading economy extend beyond mere economic prosperity. Authoritarian regimes, for example, may exploit the substantial government revenue from taxes to fund military operations abroad or sustain domestic propaganda campaigns, using their economic dominance to cement their authority and project power internationally.

As we look to the future, populous nations like China and India are on the cusp of realising immense economic power due to their large populations and burgeoning economies. Their approach to integrating democratic values, human rights, and the rule of law will crucially influence their international relations and role on the global stage. The commitment to these universal principles is essential for fostering peaceful and cooperative international relations.

Yet, the rise of these economies also carries the risk of geopolitical tensions if they do not improve their democratic and governance standards. Vigilant monitoring of their policies will be essential to navigate the potential challenges their economic ascension may pose to global diplomacy and peace.

Despite the prominence of these large economies, it’s vital to consider the internal quality of life they offer their citizens. Russia, for instance, despite being the 11th largest economy, may not provide a standard of living comparable to smaller economies like Norway, which boasts a significantly higher quality of life. This highlights the necessity of evaluating nations not just by their economic size but by factors such as income distribution, social welfare, and overall well-being.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of a country’s economic standing, one must look beyond gross economic output. Delving into per capita income, which offers insight into the distribution of economic wealth among individuals, reveals much about the standard of living and prosperity within a nation. This approach underscores the complexity of assessing economic performance, emphasizing the importance of a multifaceted analysis to truly grasp a country’s economic and social health.

Three-column table listing rank, country, and GDP per capita in U.S. dollars for 2025.

| Rank | Country | GDP Per Capita (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luxembourg | 120,000 |

| 2 | Switzerland | 85,000 |

| 3 | Norway | 81,000 |

| 4 | Ireland | 79,000 |

| 5 | Qatar | 75,000 |

| 6 | United States | 70,000 |

| 7 | Singapore | 65,000 |

| 8 | Denmark | 60,000 |

| 9 | Australia | 58,000 |

| 10 | Sweden | 57,000 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 56,000 |

| 12 | Austria | 54,000 |

| 13 | Finland | 53,000 |

| 14 | Germany | 51,000 |

| 15 | Belgium | 50,000 |

| 16 | Canada | 49,000 |

| 17 | United Kingdom | 48,000 |

| 18 | France | 47,000 |

| 19 | Japan | 46,000 |

| 20 | Italy | 45,000 |

Observing the table above, a striking trend emerges: many of the world’s largest economies vanish from contention when considering per capita GDP, revealing a stark disparity in income distribution. Conversely, nations previously overlooked in discussions of economic giants now emerge prominently, boasting higher per capita incomes despite their absence from the top economic echelons.

Returning to our scrutiny of the globe’s top 20 largest economies, a disconcerting reality unfolds as we examine their per capita income figures. Despite China’s position as the second-largest economy globally, its per capita income languishes below the world average at $9770. Similarly, India, flaunting the 5th largest economy, grapples with widespread poverty, evident in its meager per capita income of approximately $2000. Even Russia, ranking 11th in economic magnitude and often wielding influence on the world stage, falls short of the global average in terms of per capita income.

Yet, the narrative takes a transformative turn when we broaden our perspective beyond the top 20 economies. Many nations, hitherto overlooked in discussions of economic might, now shine brightly in terms of per capita income. Among the roughly 180 countries represented, Russia occupies the 57th spot, China the 64th, Turkey the 70th, and India an alarming 137th in per capita income rankings.

This glaring incongruity underscores the fallacy of assessing economic prosperity solely through sheer size. While a robust economy is undoubtedly essential for a nation’s progress, genuine prosperity manifests in the well-being and standard of living experienced by its populace. By delving into metrics like per capita income, we gain invaluable insights into a country’s economic landscape and the realities confronting its citizens.

Analysing per capita income offers a nuanced understanding of countries’ economic performance beyond mere economic size. Expressing these figures in dollars allows for a standardised comparison across nations, providing valuable insights into each country’s economic standing. However, it’s essential to recognise that using dollars as a common denominator doesn’t capture the full picture. The purchasing power of a dollar varies significantly from one country to another, rendering a direct dollar comparison somewhat misleading.

Three-column table listing rank, country, and GDP per capita in U.S. dollars based on purchasing power parity (PPP) for 2025.

| Rank | Country | PPP GDP Per Capita (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luxembourg | 140,694.70 |

| 2 | Singapore | 131,580.40 |

| 3 | Qatar | 114,929.50 |

| 4 | Ireland | 112,769.30 |

| 5 | Switzerland | 96,788.80 |

| 6 | United Arab Emirates | 88,489.00 |

| 7 | Norway | 114,049.20 |

| 8 | United States | 76,027.60 |

| 9 | Brunei | 85,011.10 |

| 10 | Hong Kong | 69,072.30 |

| 11 | Denmark | 74,897.00 |

| 12 | San Marino | 85,235.00 |

| 13 | Iceland | 69,615.50 |

| 14 | Macau | 61,231.00 |

| 15 | Sweden | 65,157.00 |

| 16 | Netherlands | 65,088.50 |

| 17 | Austria | 62,597.10 |

| 18 | Germany | 61,585.00 |

| 19 | Australia | 60,887.10 |

| 20 | Belgium | 60,735.60 |

For instance, consider the disparity in living costs between different countries. In India, a simple haircut may cost $1 at a local barbershop, while the same service could amount to $10 in the UK. Similarly, the rent for a two-bedroom apartment in an average UK city might total $1300, whereas a similar dwelling with a stunning sea view in an elite district of Izmir, Turkey, could be as low as $450. Moreover, the affordability of goods and services, such as technology products, also differs between developed and developing nations.

To shed light on this disparity, The Economist magazine introduced The Big Mac Index, which examines the price of a Big Mac sandwich across countries to gauge the purchasing power of the dollar. Similarly, institutions like the World Bank adjust and rank per capita incomes by factoring in the purchasing power parity (PPP) of the dollar in each country. This recalibration often leads to shifts in countries’ rankings, highlighting the relative differences in living standards.

For example, when considering PPP, Turkey’s per capita income ranking ascends from 70th to 51st place, reflecting a more accurate assessment of its citizens’ purchasing power. Conversely, Russia’s position in the ranking sees a marginal change, climbing from 57th to 54th place, mainly due to the high cost of living, particularly in urban centers like Moscow. Meanwhile, China’s ranking experiences a notable decline, dropping from 63rd to 73rd place when accounting for the purchasing power of the Chinese yuan.

Certainly, delving into the purchasing power of the dollar has expanded our understanding. However, our evaluation of economic performance is far from complete. The subsequent inquiry we must pose is crucial: while per capita income figures give us an insight into average income within a country, do they accurately reflect how income is distributed among its populace? The unequivocal answer is no.

Let’s take Turkey as an example, where the reported per capita income is approximately $9,000. But how many individuals within the population actually earn this amount annually? Sadly, very few. This stark reality underscores the pressing need to examine the fairness of income distribution within a nation. To scrutinize this aspect, statisticians utilize a metric known as the Gini Index.

Four-column table listing rank, country, Gini coefficient, and year of measurement. Lower Gini values indicate more equal income distribution.

| Rank | Country | Gini Coefficient | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Slovakia | 21.6 | 2023 |

| 2 | Slovenia | 23.4 | 2021 |

| 3 | Czech Republic | 24.0 | 2021 |

| 4 | Belarus | 24.4 | 2020 |

| 5 | Ukraine | 25.0 | 2020 |

| 6 | Norway | 25.1 | 2021 |

| 7 | Finland | 25.7 | 2021 |

| 8 | Belgium | 25.9 | 2021 |

| 9 | Austria | 26.0 | 2021 |

| 10 | Sweden | 26.2 | 2021 |

| 11 | Denmark | 26.3 | 2021 |

| 12 | Iceland | 26.5 | 2021 |

| 13 | Hungary | 26.9 | 2021 |

| 14 | Germany | 27.0 | 2021 |

| 15 | France | 27.3 | 2021 |

| 16 | Netherlands | 27.6 | 2021 |

| 17 | South Korea | 28.0 | 2021 |

| 18 | Luxembourg | 28.5 | 2021 |

| 19 | Switzerland | 28.7 | 2021 |

| 20 | Canada | 29.0 | 2021 |

Four-column table listing rank, country, Gini coefficient, and year of measurement. Higher Gini values indicate less equal income distribution.

| Rank | Country | Gini Coefficient | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 63.0 | 2014 |

| 2 | Namibia | 59.1 | 2015 |

| 3 | Suriname | 57.9 | 1999 |

| 4 | Zambia | 57.1 | 2015 |

| 5 | Eswatini | 54.6 | 2016 |

| 6 | Mozambique | 54.0 | 2014 |

| 7 | Botswana | 53.3 | 2015 |

| 8 | Lesotho | 53.3 | 1998 |

| 9 | Central African Republic | 52.9 | 2010 |

| 10 | Haiti | 52.9 | 2012 |

| 11 | Angola | 51.3 | 2018 |

| 12 | Honduras | 50.5 | 2019 |

| 13 | Colombia | 50.3 | 2019 |

| 14 | Brazil | 48.9 | 2019 |

| 15 | Panama | 48.2 | 2019 |

| 16 | Paraguay | 48.0 | 2019 |

| 17 | Guatemala | 48.3 | 2014 |

| 18 | Chile | 44.9 | 2020 |

| 19 | Mexico | 45.4 | 2020 |

| 20 | Costa Rica | 48.2 | 2020 |

The Gini Index assigns countries a score on a scale ranging from zero to one. A score of zero signifies perfect income equality, where every individual earns an identical share of the national income. Conversely, a score of one indicates extreme income inequality, where a single individual monopolises all income within the country.

In nations with skewed income distribution, such as many middle-income countries, the wealthiest 10 per cent of the population luxuriates in opulence surpassing even the standards of developed nations. Meanwhile, the poorest 10 per cent grapple with destitution, enduring living conditions that fall below the poverty threshold observed in some African nations.

This disparity is palpable in everyday life, especially in countries like Mexico, where stark contrasts between affluence and poverty manifest themselves vividly. One can witness affluent families residing in sprawling luxury villas adjacent to impoverished families struggling to eke out a living in makeshift tents. Such disparities underscore the pressing need for policies aimed at promoting greater income equality and socioeconomic inclusion.

The table provided above offers insights into the income distribution performance of OECD countries. Upon careful analysis, several noteworthy observations emerge. Firstly, there appears to be a concerning trend of poor income distribution among nations occupying the pinnacle of the global economy, boasting sizable economies and high per capita incomes.

For instance, let’s consider the United States, where per capita income stands at a substantial $75,000 annually. Yet, even within this prosperous economy, substantial income disparities persist. Unskilled workers earn, on average, only between $25,000 and $30,000 per year – less than half the national average. Reflecting this significant gap, the U.S. currently has a Gini coefficient of approximately 0.488, among the highest of all developed nations. While such inequality may not pose immediate existential threats in wealthy nations like the United States, it still creates notable social and economic challenges, and its effects are especially severe in economically disadvantaged countries.

Indeed, homelessness remains a pressing issue in the USA, rooted in a complex interplay of economic, sociological, and psychological factors that defy simple analysis. However, countries with robust welfare state frameworks, such as those in Europe, possess mechanisms to mitigate income disparities through alternate means.

Take the UK, for example, where income distribution appears less than ideal. Despite this, the nation affords its citizens extensive social rights and benefits. The state offers affordable housing options, provides financial assistance, and guarantees free access to healthcare through the National Health Service (NHS). This comprehensive welfare system ensures that even amidst income disparities, individuals can still enjoy essential support and protection, significantly reducing the adverse effects typically associated with economic inequality.

To better understand the nuances of income distribution within developed nations, it’s essential to evaluate each country individually. This reveals that countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark tend to offer a higher average quality of life compared to nations like England and Spain.

Furthermore, within the realm of income distribution, disparities exist even among neighbouring countries. Belgium, for instance, demonstrates a more favourable income distribution landscape compared to the Netherlands. However, despite this disparity, the Netherlands outpaces Belgium in terms of overall quality of life due to its greater wealth and robust social infrastructure.

For instance, while both countries boast extensive railway networks, the Netherlands offers superior service quality across all classes, including second-class compartments that rival first-class standards in Belgium. Thus, living a second-class life in the Netherlands equates to a first-class experience by Belgian standards, highlighting the nuanced complexities of income distribution and quality of life comparisons.

If you’d like to carry out your own investigation on any of the variables we’ve discussed, whether for countries we covered or others we didn’t, I’ve listed some useful data sources for you below.

Key Resources for Macroeconomic and Societal Data

- World Bank – World Development Indicators (WDI)Offers extensive time-series data on GDP, inequality, education, health, trade, and more.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) – Data Portal

Provides global macroeconomic indicators, including inflation, growth rates, and fiscal data. - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – Data

Ideal for cross-country comparisons of income, productivity, employment, social well-being, and environmental indicators. - United Nations – UN Data and Human Development Reports

Includes human development indexes, inequality data, and sustainability metrics. - Eurostat

The statistical office of the European Union, with detailed regional economic and social statistics. - Our World in Data

A data-rich, accessible platform providing charts and analysis on global development, health, inequality, environment, and more. - Trading Economics

Offers current and historical macroeconomic data for over 200 countries, including forecasts. - National Statistical Offices

US Bureau of Economic Analysis , US Bureau of Labor Statistics